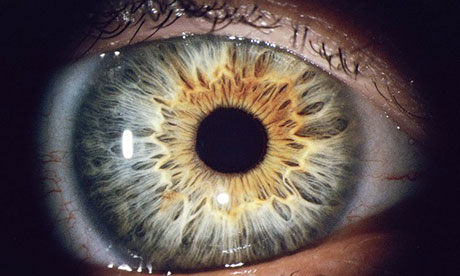

Monash scientists say their system will be the most advanced created. Photograph: Joe McNally/Getty

World-leading technology that could help restore vision to a large number of Australia's 45,000 blind people is set to emerge from a Melbourne university.

The Monash Vision system, developed by a team of 60 at Monash University, allows blind users to make out objects and other people with the aid of a brain implant that connects wirelessly to a camera which can be housed in a pair of glasses or even on the end of the user's finger.

The camera captures and sends images via a digital processor to a chip implanted under the skull at the back of the head. This chip stimulates the visual cortex via electrodes, allowing the brain to interpret the images.

The technology will allow blind people to see objects as a series of dots or solid colours. Facial recognition software lets the user identify other people, while other bespoke software, such as technology allowing users to recognise and negotiate stairs, is compatible with the system.

Monash researchers expect to release a prototype, which will be tested before being trialled on a blind person, in the first half of next year. It's hoped that the trial, if successful, will lead to the widespread use of the technology within a decade.

Project director Prof Arthur Lowery told Guardian Australia the technology was a "major breakthrough" from previous sight-giving innovations.

"It's the most advanced system created as it allows people to recognise different objects and colours," he said. "It means people can go into a meeting and know who is there and how many of them there are. People can venture outside because they can see trees."

Lowery said the sight provided would be similar to an advanced type of radar and was suited to completely blind people.

"If you have some residual vision it's probably of less use to you," he said. "You wouldn't lose the vision you had but this is only presenting a few hundred pixels and most people with residual vision have more than that. We are aiming at people who are completely blind and have brains which are hardwired to understand what objects are, rather people who have never seen anything at all."

Monash Vision was rapidly established with the aid of an $8m government grant to create the "Cochlear for vision", referring to the famed Australian invention that has dominated the hearing aid market.

The challenge was set by then prime minister Kevin Rudd's 2020 gathering in 2008.

Another team, Bionic Vision Australia, was given $42m to work on a solution which focused on replacing defective retinas.

"We thought of a different approach, one that involved a cortical implant into the back of the head," said Lowery. "You don't need eyeballs for this. If you have optic nerve damage or glaucoma this can work as it bypasses the optical system. It gives hope to people who have had serious damage to their eyes."

The project team includes Mark Armstrong, an industrial designer who created the concept for the torch at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games and was a leading designer for Cochlear.

"Mark has been a perfect fit for us because this concept is actually quite similar to Cochlear," said Lowery.

"But rather than a microphone, you have a camera at the front end. The camera could be anywhere – it could be at end of your finger, where you can scan things like your mind's eye, or you could have dark spectacles or a Bluetooth headset.

"The final users of this want something that doesn't stand out. The whole reason for assistive technology is to allow people to do many things that fully sighted people can … something that's not obtrusive."

Originally posted on: The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment